Personal Story of

David Frederick McNeley

This is David’s story, David

Frederick McNeley, my brother. It is also the story of his crew, one of the

“old crews” of the 58th Bomb Wing,” those who were first to fly

their B-29 Superfortresses against

**************

They had been training

together at

He sent the photo of that

crew in a letter dated July 2. 1944:

We

had our crew picture taken in front of our airplane today, which I will send

when it is developed. Enclosed is a picture of our former crew taken at

Front

Row: Radio Op: T/Sgt. Leo Sopata;

Right Gun-Sgt. Earl R. Sjodin; CFC-Sgt. David F. McNeley;

Tail Gun-Cpl. William M.

Mandelin; Left Gun-Sgt. Hershell O. Barrett

Back

Row: Co-pilot-Lt. Walter L. Mitchell;

Pilot-Capt. Carl T. Hull, Jr.; Bombardier-Lt. Kenneth

Alexander; Navigator-Lt. Anthony J.

Marinaccio; Engineer-Flight Officer Paul M. Clark

The letter went on to say:

Boy,

I’m really seeing the world, have been to

And then it continued, with a

hint for us:

I

can’t think of anything more to say, except that I’m well and happy and

that Jim might be pleased to know that I am a member of the catipiller (sic)

club, know what it is?

Jim was only 10 years old but

knew what his big brother was hinting at; he had bailed out of an airplane, the

flying creature becoming a land-based one, a kind of reversal of the

metamorphosis of caterpillar to butterfly.

There was no explanation

given for the crew changes or anything more about having to parachute out of

his plane. It was 55 years before we learned about two plane crashes, one

ending in the loss of six of the eleven original crew members, the other

telling the story of his bail-out.

It was on May 18, 1944, less

than two weeks after they had arrived in

Retaining just enough fuel

for the return trip, they took off from

First to go was the tail

gunner, S/Sgt Buck Blake. In opening his emergency hatch, preparing for the

bail-out, he had disconnected his intercom. Afraid that he would not hear the

order to jump, he did not wait for the order but “just went.” He landed near a

village, breaking his leg. Not knowing if the natives would think he was

Japanese, he pulled his gun to defend himself. However, when they did not come

at him with weapons he concluded they were friendly. By 10:00 p.m. they had put

him on a train which took him to an army hospital operated by the British,

somewhere on the

The other gunners left next,

by the rear entrance door of the rear compartment of the plane. Hershall

Barrett went first, then David. Robert Snow was last. They landed a few miles

from a village, later identified as

After the co-pilot and

gunners had left, Major Wagnon kept trying to find a place to land. Finally,

after the two outboard engines were out of fuel, the Navigator, 1/Lt. Helmer

Hansen, the Bombardier, 1/Lt. Loyd Burchan, and Radio Operator T/Sgt. Tom Drew

all bailed out together. Flight Engineer, M/Sgt. Alvin Lebsack set the gas

pumps working and Major Wagnon put the plane on course for the hills before

they also jumped from the flight deck.

This last group all got together

on the ground sometime after dark. Natives were hired to guide them and to

carry their chutes and jackets. They followed a railroad track west and south,

eating bananas and the food in their survival kits. After following the tracks

and sleeping alongside them for two days, they were led to a British Army camp.

It was part of the supply group that provided for Stillwell’s forces and the

The British drove them about

20 miles to a small railroad station where they bought first class tickets.

After riding for the next twenty four hours, eating food the British had given

them, they arrived at a base on the border between India and Burma, about seven

hundred and fifty miles northeast of Calcutta. Col. Kalberer, their Squadron

commander, met them in a large single engine airplane and flew them back to

their base on May 27. 3

While David and Hershall

Barrett were earning their right to join the Caterpillar Club, Captain Hull,

known as “Shorty Hull,” and the rest of their regular crew were assigned to a

training flight. It was May 24 when Capt. Hull attempted to take off. The

wheels were just off the ground when the No. 4 engine failed and the plane

stalled, crashed, and caught fire. Some of the crew tried to get out of the

upper forward astro dome but found the heat of the fire had sealed the round

rubber gasket which held it in. They escaped by using their 45's to shoot out

the blisters. Co-Pilot Mitchell, Right Gunner Earl Sjodin and the two gunners who

had taken David and Hershall Barrett’s positions, were all killed. Flight

Engineer Tony Marinaccio and Navigator Kenneth Alexander were so badly injured

they were returned to the States. The rest of the crew were injured and

hospitalized.4 The replacement gunners who lost their lives were

Lyle D. Brunson, CFC gunner, replacing David and Bazel E. Hughes, Left Gun,

replacing Hershell. David A. Eldon, who was apparently with the crew as Radar

Operator in Weinbauer’s absence, was injured, as was a “visitor,” Anthony P.

Romand.

When David and Hershall

returned to base they found the surviving members of their crew in the

hospital. With five of the eleven-member crew dead or severely injured, a new

crew had to be assembled. It included only six from the original group that had

left Walker Field:

I

found out that our navigator (Lt. Van Horn) comes from

Flight Officer Paul Clark

was flying with Col. Richard Carmichael’s crew on August 20, 1944 when their

plane was hit by an aerial bomb during the mission to

After the loss of Paul Clark,

Charley Blackburn became their Flight Engineer. PHOTO OMITTED

Only occasionally did David’s

letters specifically mention a mission that he had flown. In a letter dated

Sept. 12 he wrote:

[Have]

just gotten back from a trip over the hump . . . You can find out more about me

by reading the papers.

He was referring to what

happened after a Sept. 8 raid on

Two months later he mentioned

action during a mission for the first time:

Nov. 26. 1944

Dear

Folks:

I’m

very sorry that I haven’t written sooner but, I’ve been fairly busy. Our crew

was on the last Omura mission, and I really enjoyed it. The Japs threw up every

thing but it wasn’t enuff.

We have learned what happened

on that mission, from a citation for Captain Hull that was posted on the

Internet early in 2003:

“The

Silver Star was awarded to Captain Carl T. Hull, Jr. for ‘outstanding gallantry

in action while pilot of an aircraft which was participating in combat

operations against enemy installations at Omura,

Displaying

great heroism and utter disregard for personal safety, Captain Hull with great

skill and resolution voluntarily flew as protective cover for the damaged

airplane, shielding it from many of the savage and closely pressed attacks

until such time as it flew into an undercast. His coolness and refusal to

abandon a comrade was an inspiration to all. Such disregard for personal safety

and conspicuous gallantry in action is in keeping with the highest traditions

of the Army Air Forces, and reflects great credit upon Captain Hull and XX

Bomber Command." [Need source.]

Writing on December 3, David

announced:

About

a week ago, we had a parade, and Maj. General Curtis LeMay (our Boss) personally

presented a few of us with the Air Medal. That is given for completing 100

hours of combat flying. I will send or bring this medal home in the near or

late future.

Recognition of the award to

David and four others was published in a favorite column of those days:

PHOTO OF BELIEVE IT OR NOT COLUMN OMITTED

After nearly a year in

Fresh B-29 crews had arrived

on Tinian, Guam, and Saipan in January and had been carrying out bombing raids

on

The only mission about which

we know the details was their last one, June 5, 1945, a fire raid on

From the Missing Air Crew

Report, we know how the plane was shot down, as described in a witness

statement by Pfc. James L. Bucklin:

I

was left gunner in aircraft No. l329, which was flying #7 ship in the

formation. After we had left the target and were heading for the turning point,

aircraft No. 44-69965 [

“As

they made the first turn away from the target, #965 was still close enough to

receive protection from us. The fighter attack at this point was very

concentrated. As we made our turn toward the coast, #965 was approximately 800

yards out at 7 o’clock from our ship. Our altitude at that time was 15,500

true. About two or three minutes from the second turn, two Nicks worked around

the formation and attacked #965. Several coordinated attacks were executed by

them.

“A

smoldering fire had existed on #965's number two engine up to this time. After

the fighter attacks, #965 began to blaze fiercely and it was evident that the

ship would not make it. I saw three chutes open up. Then a great sheet of flame

enveloped #965 and the left wing fell off. Both wing and plane were burning as they

tumbled toward the earth. Five more chutes opened in a bunch, making a total of

eight (8). Shortly afterward the ship hit the ground and exploded.”

The first report of the crash

gave the location as 35 miles southeast of the target, which would

have been on land, ESE of

Osaka. However, Japanese eye witness reports on the ground tell

a different story, as we

shall see.

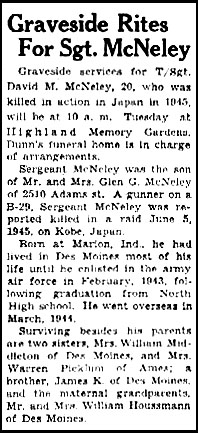

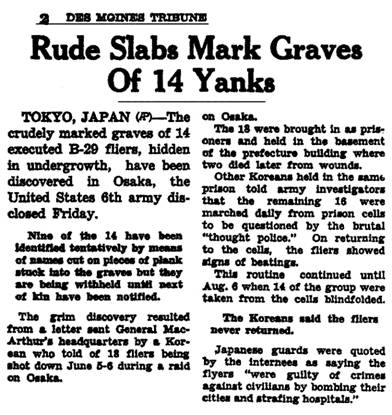

The telegram did not come

until July 2nd, and the news article announcing it was published

in the Des Moines Tribune July 5, 1945. It was just the first in a series

of news clippings that marked the long wait for news of those who were missing-in-action.

They reflect the growing despair of the families that waited for news of their

fate.

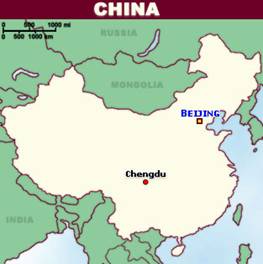

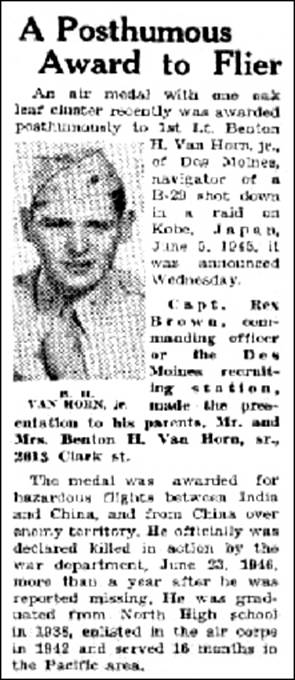

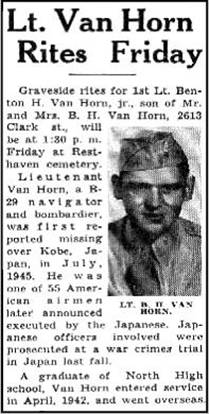

Posthumous medals were presented

to Benton in March, 1947 and to David in February, 1947, as below:

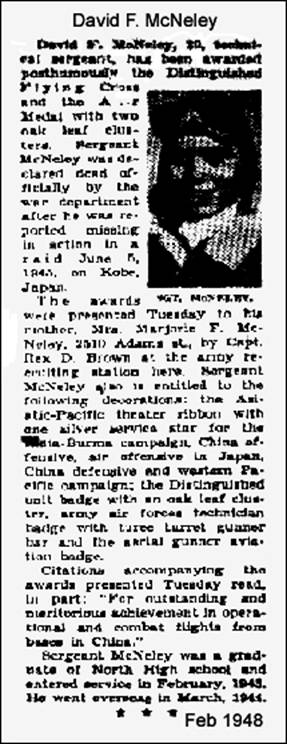

The fate of Benton and others

who had been taken prisoner was published in the Des Moines Register Sept 1,

1948:

The

press release obtained from the Des Moines Register did not list David among

the 55 who had been executed as the war ended. Besides Benton Van Horn it did

list several of the other crew members. The list was composed for the War

Crimes Trials using information then available, and was later found to have

contained several errors.

Benton

Van Horn’s body was one of five found in Sanadayama Military Cemetery Grave 3, a group known to have been executed August 15 or 16,

1945, as the war was ending. He was identified by his ID bracelet which had his

name on the outside and on the inside, “Love - Dad Mother Shorty Ellen” His

body was sent home for burial in September, 1949.

David was finally identified

as one of those who had been taken prisoner and, like

The story of the loss of

“Shorty”

“...

Major Carl T. ”Shorty Hull . . . had already completed his 35th

mission and was grounded until (General)

“Vaucher

was heartsick about

The crew, however, was not

immediately executed, although that did occur in other cases and was what the

Japanese had warned would happen to B-29 crews if they were captured. The truth

about the crew’s fate is documented in testimony taken in connection with the

Tokyo War Crimes Trials. That story follows, summarized from several sworn

statements by eye witnesses.

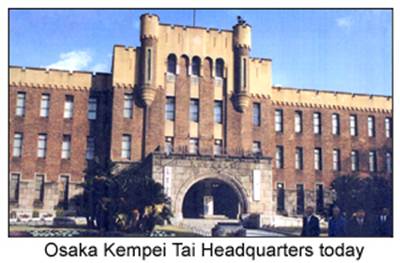

INVESTIGATION OF INDIVIDUAL CASE #405

B-29 Crash Near Nu Island on 5 June 1945

23 May 1946

1.

Between 12 April and 17 May 1946, an investigation was conducted on individual

case # 405, which is connected with the Osaka Kempei Tai case. . . .The

following information was obtained regarding the crash and subsequent events.

2.

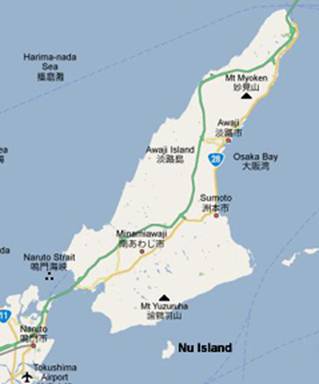

At approximately 2250 hours on5 June 1945 a B-29 crashed about one mile east of

Nu Island in

3.

Survivors – Five crew members parachuted from the plane and landed in

None

of the fliers was injured.

That

night the fliers slept at the Yura Kempei Tai and next morning, 7 June 1945,

between 0600 and 0700 hours, the five fliers left for

4.

Identity of the Plane - - the plane was identified by two means; First, the

Missing Air Crew Reports listed B-29 No. 44-69965 as having crashed on 5 June

1945 about 35 Miles Southwest of Kobe. (Note the corrected direction from

Following Is a Complete List of the

Crew:

1. Pilot

2. Co-pilot Moser,

Cletus W 1st

Lt

3. Navigator Van

Horn,

4. Bombardier Stewart, Oliver M 1st Lt

5. Flight Engr

6. Radio Op. Drew,

Thomas O T/Sgt

7. Radar Op. Weinbauer,

Arthur H S/Sgt

8. CFC Mcnaley (Sic), David F T/Sgt

9. Right Gunner Barrett,

Hershell D S/Sgt

10. Left Gunner Zinn,

John N S/Sgt

11. Tail Gunner Clemens, James H

S/Sgt

5.

Disposition of the dead – the six crew members who were not picked up in life

rafts must have been killed in the crash or else drowned afterwards. To date no

evidence of them has been found, and it is doubtful that any will be found. At

present it seems safe to assume that everyone beside the five survivors

mentioned in Par. 3 above were killed in the crash or shortly afterwards.

6.

No evidence of mistreatment of the five survivors was obtained up to the time they

were turned over to the Osaka Kempei Tai Headquarters.

Because eight parachutes had

been seen to leave the plane, it was later concluded that three must have

gone down with the plane in

A group of three parachutes

had been seen leaving the plane, in addition to the group of five that landed

near Nu Island, leading to the conclusion that the remaining three apparently

drowned.

Identification of the two

captured noncoms was possible because of a remarkable letter from Kiyoji Nakamura,

written to General Macarthur in January 1948:

I

express my sincere appreciation to the United States Government and to General

Macarthur.

During

the war, I was a policeman of Hyogo Ken, Awajishima, Yura.

After

the war, upon being discharged from the Police Force, I moved into the address

indicated on the envelope. I am worried about the welfare of the men who

survived the wreck of the B-29 which flew over

About

1330 Hours on 6 Jun 45, after a raid over

At Yura Fortress, after a brief investigation, a meal was to be prepared for them, but, having no mess funds, I talked with the Fortress Commander about securing wheat meal and side dishes from the villagers. The Fortress Commander gave fruits to the crew members who had by then lost all desire to fight.

(1) Date and Time of Bombing: 1045 Hours, 6 June 45. (An Error: it was 5 June)

(2) Date and time of Capture: 1300 Hours, 6 June 45.

(3) Names of Crew Members:

1st Lt. Banaton Fuwasunebanki, 25 Years Old.

M/Sgt. Atsu Hichibawain, 23 Years Old.

Radar Operator Jon Unugin, 23 Years Old.

Haseru De Bazetto, 28 Years Old.

M.Sgt. Gunner Rabitto Efu Mekumeri, 20 Years Old.

The other six members presumably drowned.

1

The

above five persons were taken to the Osaka MP Headquarters by Kura MP

Detachments, 7 Jun 45.

According

to the MPs, there were in

The above facts are given for your information,

1[2?] Jan 48

Ajiko 214[?]

Nakamura, Kiyoji

Although the five were now

known to have been captured, their bodies had not been found in any of the

known graves of prisoners. It was not until yet another witness came forward

that a hidden grave was located.

Oliver Stewart’s family heard

about their son’s fate in December, 1951 when his father received the first

communication from the War Department since 1945. His son’s body had been

identified as one that had washed up on shore about 20 July 1945, at Kannoura

Machi, Aki District. The grave was marked with a board bearing the inscription

in Japanese characters, “American airman killed in action.”

The date on the following

article was not noted when David’s family clipped it from the

The group of prisoners was

then linked to a group that had been executed on or about August 5, 1945. They

were taken in two groups of seven fliers, one-half hour apart, to the Jonan

rifle range, adjacent to the headquarters of the Fifteenth Area Imperial

Japanese Army at

In November 1951 David’s body

was identified as one of those in that mass grave. The graves registration

experts had previously identified all but one of the five from

Today the site of the Jonan

Rifle Range is a field where boys play baseball, adjacent to a

Research and Text by Neysa

McNeley Picklum;

Graphics and website created

and formatted by Claradell Shedd; 12/30/09